Andrew Wyeth would have celebrated his 100th birthday this year. This Centennial has prompted some long-overdue reassessment of his artistic legacy.

In 1991, I was 35 years old and coming off of a successful show at PPOW Gallery when on the next to the last day of the exhibition art critic Roberta Smith wrote a negative review of the work in The New York Times.

I had a strict rule of not reading any of my reviews good or bad. But Wendy from the gallery encouraged me to go out and buy the paper and read the review, because, she said, I would need to “be aware of what people would be saying about the work.” Reluctantly, I did as my gallerist instructed. Although it stung, I didn’t really care about the review at the time. But, the following months shed a different light on the negative ramifications of bad press. Several scheduled articles dried up. Sales slowed to a trickle. I found myself in need of appreciation and resources.

It was at this moment that my life took an unexpected turn. A catalog from my exhibition had made its way to Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania and into the hands of Betsy Wyeth, wife of the most famous living American artist at the time, Andrew Wyeth.

Rumor had it that she had read the review in the Times, and being a proponent of American Realism, she had invited me out for a visit. Betsy Wyeth was full of encouraging words about the work. Perusing the exhibition catalogue she noticed in my bio that I’d been to film school at NYU. She asked me if I’d help her make a film about her husband. I’d been out of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts for over 10 years and had never had a day job since graduating, but, this seemed like a fortuitous proposition.

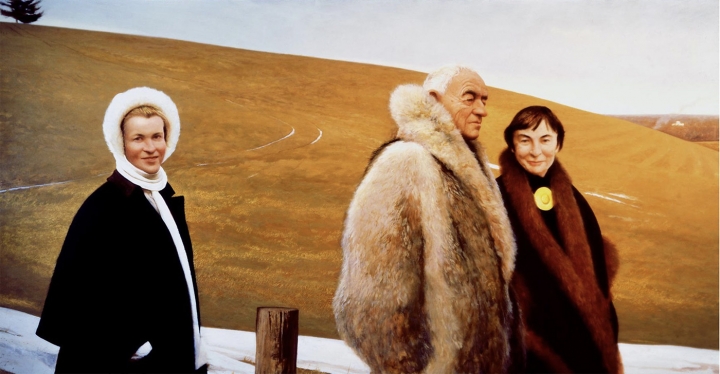

Betsy and Andrew Wyeth on Benner Island, Maine, 2006 (photo Bo Bartlett)

One of the reasons I’d moved to Pennsylvania from my native Georgia 15 years earlier was to try to study privately with Andrew Wyeth. Upon arriving in Pennsylvania in the mid-1970s I’d spoken with him on the phone and he let me know that he didn’t accept private students. So I entered the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) and through a broader lens of American Art learned my own way of interpreting the world in paint. I had been taught at PAFA to stay away from “illustrators” and “draftsmen” like Wyeth. We were taught that such artists weren’t “painterly” enough and that their “handiwork” was just “skill” and “craft,” words shunned at the time as not “Modern” enough to be taken seriously by the Art World.

I had bought wholeheartedly into my art training, and when invited out to the Wyeth’s, I was honored but skeptical. Obviously, I knew more about art than this regionalist who had made it no further in his education than first grade, but circumstances dictated that I needed to take the job, so I began to help Mrs. Wyeth make a film about her husband.

Over the next four years, I spent every day with the Wyeth’s — from 9 am till sunset. We became fast friends. Not only did I have a secure paying job, but the Wyeth’s loved my work and were very supportive, buying paintings and encouraging me in my endeavors every step of the way. This praise and encouragement certainly was a salve that washed away the sting of an art critic. During these years I began to de-program myself from my art school training. Slowly, the scales were scraped from my eyes and I saw clearly what I’d once known, that the best paintings of Andrew Wyeth were indeed masterpieces, and each piece was a unique representation of his experience. He painted his own backyard, literally, in Maine and in Pennsylvania. He didn’t care if it was “abstract” or “realistic,” he didn’t make such useless distinctions. He didn’t come up with an idea and illustrate it. He would walk out of his house each morning and with eyes wide open he would experience the world, like a zen master, he would just look and be.

When he saw something that excited him he would reach for pencil and paper and do a quick sketch. If it continued to interest him he would do a more finished drawing. If his interest was not yet quenched he would grab his watercolors and add color. And if he had not thoroughly investigated what was before him, if the curiosity of his subject still wasn’t sated, he would get a panel and start a more detailed tempera painting. It wasn’t about “making Art,” he was just painting his life, recording his world.

Helga, Andy, Betsy in Barlett’s “Painter’s Crossing” (1996)

He didn’t even title his paintings. His hunger to get it down was voracious and the resulting work was veracious. There was no intention whatsoever of pandering, not to a public, or a dealer, or a critic. He painted for himself and for his wife, Betsy. (And in later years, to Betsy’s chagrin, he collaborated with his model and muse Helga Testorf.) But in the end, it was a solitary act. Andrew Wyeth taught me what art is all about. I may have learned “how” to paint somewhere else, but I learned “why” to paint in Chadds Ford with Andrew Wyeth.

After a long day of working on the film — which became the documentary SnowHill (1995) — with Betsy, she’d invite me back over to their home, the Mill, and we’d all spend long evenings together eating, drinking, drawing, and talking art.

Andrew Wyeth had a vast knowledge of art, all art, ancient, classical, traditional, realism, abstract, modern. He enjoyed learning of new younger artists that he wasn’t familiar with, and he introduced me to artists with whom I was unfamiliar. We loved these exchanges. We drew one another. I asked him once how he stayed motivated over his long career, and in natural Wyeth obtuse fashion, he answered, “I’ll be going along and I’ll see a piece of barbed-wire with a piece of horses mane stuck on it, and it’ll just get me going.”

It is hard to imagine in these fast-paced internet times anyone slowing down enough to get excited by a piece of hair on a piece of barbed-wire, but this was the modus operandi of Andrew Wyeth. He painted what excited him. It was that simple. Andrew Wyeth had great courage. He didn’t let others dictate his path for him. He was true to himself. We were best friends right up until his death in 2009.

A sketch of Andrew Wyeth by Bo Bartlett

I’d last seen him in October of 2008, I was working on a small documentary film (SEE) and he’d agreed to have a little cameo. We enjoyed a meal together at Farmer’s Market in Tenant’s Harbor Maine — just me, my wife (artist Betsy Eby), Andy, and Helga. We filmed the whole meal. We talked shop and other artists and our latest paintings and our health and our life. We all assumed that there would be many more meals to share in the future. He was 92 but as sharp, playful, and chipper as a twelve-year-old boy. The very next week, he had been sitting for long hours painting outside when he stood up and had a serious fall. Medical complications in the following months led to his death. The world has not been the same since his passing. Just ask anyone familiar with Midcoast Maine or Pennsylvania's Brandywine Valley and they’ll tell you some magic is missing.

Andrew Wyeth was my artistic father, my mentor. I think of him every day. I am grateful for our time together. I think of him as I make studies or plan a painting. I think of him as I paint. I think of him as I meet and encourage students and younger artists. The last time I saw him, outside of Farmer’s Market, the camera was still rolling as we said our goodbyes. We hugged and he waved back laughing. His last words to me were, “Keep yourself free!” In these times of uncertainty and cooption, may this last charge be an empowering mantra for us all.

This article was originally published July 12, 2017, in HyperAllergic